Donald Lipski’s most recent work of public art was unveiled earlier this month as part of the opening of Philadelphia’s new Public Safety Building which houses the Police Department Headquarters, Police District 6 and 9, the Medical Examiner’s Office, and 911 Call Center. In 2019 Lipski was selected to create a work of art for this iconic building which was previously home to the Philadelphia Inquirer Newspaper. The location selected for the artwork allowed for it to be viewed when in the building’s lobby and from the exterior on Broad Street looking in.

An early rendering of Donald Lipski’s initial design for the Philadelphia Public Safety Building.

Lipski was first drawn to this project because of his love of Philadelphia. When it was time for his son to enter high school Lipski and his wife, Terri Hyland, moved from Sag Harbor to Philadelphia with their son Jackson so he could experience life in a larger city. This move only furthered Lipski’s love of Philadelphia and when the opportunity arose to create a work of art for an iconic Art Deco building that was undergoing renovations to become the new Public Safety Building he was all in.

The Art Deco tower built at 400 North Broad Street was originally built to house the Philadelphia National Inquirer Newspaper and now houses the newly renovated Public Safety Building.

His initial design was a massive badge, studded with thousands of actual Philadelphia Police Department badges representing all of the ranks. The suspended sculpture would be double-sided and face both visitors and staff in the building’s lobby as well as pedestrians and motorists on Broad Street. This design was selected and approved by the Police Department and the Philadelphia Arts Commission.

An early rendering of Donald Lipski’s initial design for the Philadelphia Public Safety Building.

Then in 2020, in a world already in turmoil from the Coronavirus pandemic, the police slaying of George Floyd and so many other people of color put tremendous strain on the trust that is needed between the police and the community. At this moment Lipski had to pause and think if he even wanted to make a sculpture for the police. In Lipski’s words,

“I had presented the badge as a ‘shield’, a source of protection. But I was soon reminded that for large groups of Philadelphians the badge is instead a symbol of oppression and fear. I set about trying – by a symbolic re-design – to change that.”

The stated purpose of a Police Officer’s badge is, “…a symbolic emblem given by The People as a show of Public Trust. It represents Honor, Integrity, Truth, and Justice. It’s a symbol of Service to the Community.”

A close up of one of the 1,400 badges affixed to the final sculpture.

The seal of Philadelphia is the central image in the City’s flag, can be found on many public buildings, and is the focal point of every Philadelphia Police Department badge of every rank, from Officer up to Commissioner. Lipski began delving deeper into the seal and its history and set about making this modified seal a symbol of inclusivity and a reminder of what the badge is supposed to stand for. Something for the 1,200 employees who enter this building daily to look to as a symbol and a reminder of what the badge is intended to represent. He knew he wanted to retain some elements of the original seal including the plow and sailing ship which represent the joining of Chester County, a place of agriculture, and Philadelphia County, a place of commerce, retaining these elements from our history while looking toward the future.

Lipski came to find that over the years the seal has been represented in a lot of different ways and in some paintings of the seal artists used actual Philadelphia women to represent the two classical female figures representing Peace and Plenty. In the original seal Peace, on the left, holds a scroll that originally depicted William Penn’s 1682 street plan. This was used as a symbol of Peace since Penn designed a city without any fortifications, determined to live peaceably with the indigenous populations of the area.

City of Philadelphia Coat of Arms by Thomas Sully, circa 1821.

In Lipski’s redesign, the figure of Peace is represented by Lucretia Mott, an abolitionist, pacifist, and women’s rights advocate. In 1833 Mott was one of the founders of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and in 1848 she organized the Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Mott helped to pen the Declaration of Sentiments which was presented at the convention and demanded rights for women by inserting the word “Woman” into the language of the Declaration of Independence, along with a list of 18 woman-specific demands.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.”

In Lipski’s reimagining of the seal, he wanted to add something to the scroll held in Mott’s hand that would be more direct in its symbolism of peace. Thanks to a recommendation from his son Jackson, Lipski added this quote from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“True peace is not merely the absence of tension: it is the presence of justice.”

Detail image of Lucretia Mott from Let Love Endure.

Detail image of Let Love Endure.

The figure to the right of Peace, representing Plenty, is now Frances Harper, Philadelphia abolitionist, suffragist, and poet, one of the first African American women to be published in the United States. In 1858, a century before Rosa Parks, she refused to give up her seat or ride in the “colored” section of a segregated trolley car in Philadelphia. The cornucopia in Harpers’ hand which holds fruits and vegetables in the original seal now overflows with tokens representing Housing, Education, Health, and Liberty.

Detail image of Frances Harper from Let Love Endure.

Detail image of Let Love Endure.

The scroll at the bottom of the seal was added to the design in 1874 with the City’s motto: Philadelphia Maneto, which means: “Let Brotherly Love Endure.” After a conversation with Philadelphia’s Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw, Lipski decided to remove the reference to gender from the original scroll which in his redesigned work now reads simply, “Let Love Endure.” This then became the title of the work.

Let Love Endure, Donald Lipski, 2021

The sculpture is studded in over 1,400 actual police badges all given the number 2020 to remind us of this historic year, which like 1776 will be regarded as a pivotal time in our history. 2020 was also the 150th anniversary of the 15th Amendment, which granted Black men the right to vote, and the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote.

Brenda Exon’s reimagining of the Philadelphia flag.

Lipski’s work on this project connected him to Brenda Exon, a Philadelphia-based educator, and big Philadelphia flag enthusiast. Years ago Exon set out to teach students about the history of the flag, its many iterations, and what it stands for. She reached out to the Humphrys Flag Company, a company that Lipski worked with in 1990 when he did a flag show in Philadelphia with the Fabric Workshop, and had them update the City’s flag so one of the two women depicted was African American. Exon would then take this flag into the public schools in Philadelphia and show it to the students and the response from young black students was incredible as they finally saw themselves represented in the City’s seal.

Lipski is hoping to connect with Philadelphia Public Schools to find a way to teach students about this work of art in the classroom so that when they see it someday as they walk down Broad street it will create a welcoming feeling of inclusivity.

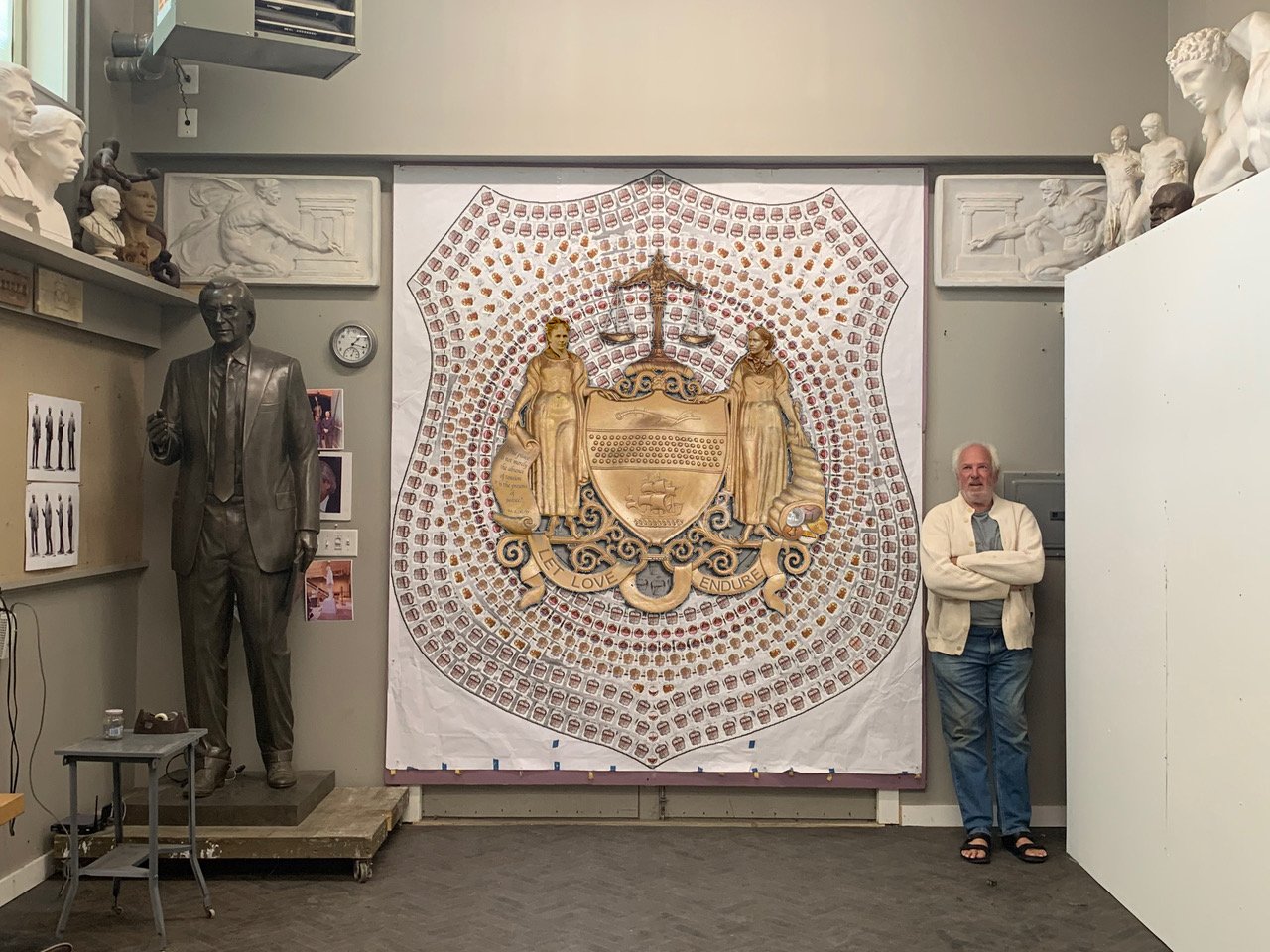

Donald Lipski standing next to a mock-up of Let Love Endure in Philadelphia sculptor Christopher Collins’ studio.

To learn more about this project visit www.creativephl.org/let-love-endure-donald-lipski/